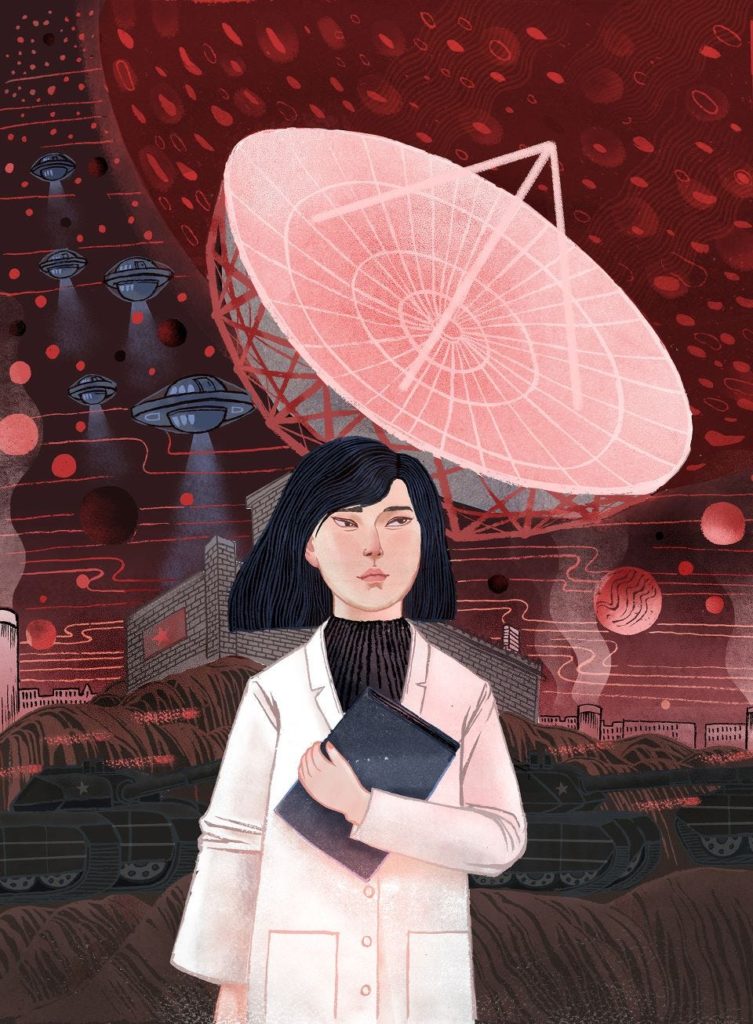

On Cixin Liu’s “The Three-Body Problem”

“The Three-Body Problem” is the first installment of a science-fiction trilogy by Chinese author Cixin Liu. Praised by international elites like Barack Obama and Mark Zuckerberg, “Big Liu”, as he is known in the Chinese sci-fi community, was notably the first Asian author to ever win the Hugo Award. After China receives a warlike transmission from an alien civilization, “different camps [on Earth] start forming, planning to either welcome the superior beings and help them take over a world seen as corrupt, or to fight against the invasion.” I took this quote from the American translation blurb, but to be honest, I think it paints too vague a picture. Three-Body comes off as dramatically futuristic, with an overabundance of life-threatening situations and existential conversations. In reality, this novel does explore the age-old trope of alien invasion, but with a story of immense scope. It observes the geopolitical consequences of scientific breakthroughs alongside trauma’s echoing effects on individual worldviews, all weaved together in a cold, scientifically intricate narrative. Despite Liu repeatedly stating that his stories and scientific premises are not based in reality, readers are always at liberty to form their own interpretations of fiction. So, what makes this tale so alluring to world leaders, tech giants, aerospace engineers, the Chinese, and Americans alike?

Three-Body begins with a flashback to the Cultural Revolution in China, an era of political mobilization and ruthless persecution. The opening scene describes in painful detail the struggle session of a theoretical physics professor. His former students, now indoctrinated into the Red Guard, beat him furiously and command him to denounce his life’s work as it is considered reactionary. He refuses again and again and eventually dies for his sanity and the undeniable truths of science. Amidst the blood-crazed frenzy that ensues, his daughter, Ye Wenjie, hardens her heart forever to all hope in the goodness of humanity. After being captured and relocated to a military research base, Ye, an astrophysicist, places her faith in the stars, yearning for an interstellar intervention to cleanse the planet of its corruption.

In the present, information obtained by Ye’s transmissions at the base spreads like wildfire throughout global scientific and social elite networks. Factions that declare loyalty to the alien cause proclaim an equal hatred for themselves, their children, and the rest of humankind. These people despise the dark side of human nature more than they cherish the innate dignity of life. It is too unrealistic to imagine.

Liu emphasizes time and time again the middle and lower classes’ inability to embrace the importance of such a discovery. For normal people in Liu’s society, ignorance is bliss. They are pawns, incapable of influencing technological progress and, consequently, the fate of humanity. Whether Liu excludes “common people” from intellectual discussion for literary effect or out of technocratic arrogance does not matter; the narrator’s lack of faith in human connection and perseverance is disturbing and prevalent throughout the entire novel.

Equally frightening are humanity’s perverted feelings of “spirituality.” A faction known as the Redemptionists believes that it worships what truly exists as opposed to all other world religions, which, in their eyes, have failed. They look to the aliens as their gods, whom they plan to serve in the conquest of Earth. Clearly, it is completely backward to turn to religion to pursue the salvation of a higher being and not of ourselves. Religion should help us come to terms with our flaws and the unattainability of perfection, while spirituality should give us a greater sense of peace with the world, each other, and ourselves. Instead, Liu’s godless technocrats only venerate what they desire to weaponize: their own scientific prowess and an unsympathetic alien race. It is a wretched response to give up one’s self-respect in the face of an otherworldly advent. I, for one, do not believe humanity could sink this low when we have emerged from much darker times.

At the center of this saga is a cryptic VR game in which, on a strange planet, the player is tasked with deducing the elusive pattern of the rising and setting of the sun. Sometimes, the sun comes close enough to scorch the entire planet, and sometimes, it will not rise for decades. The ability to predict the sun’s mercurial cycle between Chaotic and Stable Eras (when the sun rises and sets regularly) would allow civilization to develop uninterrupted and avoid extinction. Unbeknownst to players initially, this game was created to replicate the nature of life on the alien planet. However, it fails to communicate the utter spiritual desolation that has permeated their civilization after generations of lives dedicated to survival in an inconstant world. Since Chaotic Eras decimate this species before it can thrive, they are unable to question life, think for themselves, or develop a culture. Its leaders believe that the only solution to staying alive is to eliminate all individual freedom and assign everyone a single role for the rest of their lives. In fact, the lowly alien who receives Ye Wenjie’s transmission secretly responds warning her of the hostility of his species. He himself can see the preciousness of life on Earth from light years away, but after centuries of bloodshed and upheaval, victims like Ye have lost this perspective. Unlike the aliens, humanity does not rise and fall with the sun. Unlike the aliens, we can devote ourselves to individual leisure, love, and intellectual pursuit. The sad thing is, as historical revolutions show, for better or worse, we crave the novelty of rebellion so deeply that we blind ourselves to the dehumanization and destruction it is sure to bring. What will happen when we, as a race, are rendered powerless to decide our own fate?

Of all the possibilities, Liu’s answer to the Fermi paradox is pretty unsettling. The narrator sums it up nicely with the theory of “contact as symbol,” as proposed by fictional sociologist Bill Mathers. Mathers believed that contact with an alien civilization was a mere trigger for inevitable results. The revelation of alien life alone is enough to push mass psychology and culture in an entirely new direction. He continued on to theorize that a single entity’s control over communication with the aliens “would be comparable to an overwhelming advantage in economic and military power.” An empowered technocratic class leads Liu’s society through the dark, but what good is this authority if it is not composed of empathetic, relatable figures who will speak and act for normal people? Or is this idea that anyone can make a difference simply a trope exclusive to Western, democratic-minded science fiction? Liu, evidently, does not value this idea, but nevertheless, his work demands respect in that it directly questions the validity of our beliefs. In the future, everyone, Chinese and Americans alike, will want a role to play if aliens do come, but who gets to determine these roles? Liu imagines the elite, as do Obama, Zuckerberg, and others. I like to imagine that humanity will be greater than the sum of its parts.

I love this article, I can’t wait to read more by you ❤️

Why thank you MalinkyZubr:)

But of course Guinevere

Greetings! Very helpful advice in this particular article! Its the little changes that produce the largest changes. Thanks a lot for sharing!